Me standing around outside work, frowning.

In September 2013, I moved to 'that London' to pursue my new career as a class-traitor and absolute disgrace. Jettisoning those moving pictures I had once cherished so, I began a ceaseless and disgusting flirtation with their posh sister, West End theatre, whilst revelling in the perks of my job as Press Executive at the universe's premier music venue, the Royal Albert Hall. That's why this review of 2014 takes in not only my film viewing but also, for the first time, such things as plays, exhibitions and concerts. We'll start with the movies, though in time-honoured tradition...

***

FILMS

16 best discoveries of 2014, in descending order of utter, jawdropping brilliance:

%2BBluRay%2BCriterion%2BCollection%2BAC3%2Bx264.mkv_snapshot_01.23.14_%5B2011.06.10_00.38.53%5D.jpg)

Sommarnattens leende (Ingmar Bergman, 1955) aka Smiles of a Summer Night - Bergman does sex comedy - and the result is a deep, delicate, just about perfect movie, like the best of Lubitsch and Ophüls mixed with Partie de campagne.

Jeux interdits (René Clément, 1952) aka Forbidden Games - The children are both sensational, and the scenes concerning their obsessive friendship, their darkly comic quest and their wrestling with the biggest and most troubling questions in life are singularly and enduringly resonant, leading to a final scene that's as moving and powerful as cinema is ever going to get.

The Miracle Woman (Frank Capra, 1931) - By far the best of the five collaborations between future It’s a Wonderful Life director Frank Capra and the mercurially gifted Barbara Stanwyck: a blistering, beautiful Pre-Code masterpiece. Her final speech on the stage that may well be the best thing she ever did - at which point I should add that she stars in my favourite film of all time, Mitchell Leisen's Remember the Night.

Another Country (Marek Kanievska, 1984) - If you're interested in British history, class or sexual politics, it's completely fascinating, invigoratingly entertaining and extremely moving, with a hypnotically powerful, well-conceived pay-off.

Nightmare Alley (Edmund Goulding, 1947) - A stunning, staggeringly cynical melo-noir-ma about an amoral carnival huckster (Tyrone Power) using everyone he meets as he cuts a rapid path to the top. Gripping from first frame to last, it's simply one of the best of its decade: richly atmospheric, incisively intelligent and both fatalistic and unpredictable in the best tradition of the genre.

When the Wind Blows (Jimmy T. Murakami, 1986) - Hell. A devastating animated feature about the Atomic Age from the writer and director of The Snowman, which takes Peter Watkins' seminal drama-doc The War Game as its jumping off point, showing an archetypal, retired English couple as they prepare for an approaching nuclear strike.

Jodaí-e Nadér az Simín (Asghar Farhadi, 2011) aka A Separation - A searing examination of contemporary morality that offers no easy answers and passes no shallow judgements on its damaged characters, instead giving us something akin to real life, albeit in a world that often seems so very far removed from our own

Boyhood (Richard Linklater, 2014) - Its USP is far more than a gimmick; rather, it's what enables Boyhood to create such an indelible impact: visually, viscerally and deep down in your soul.

Mud (Jeff Nichols, 2012) - I told you that Matthew McConaughey was amazing. I spent 10 years saying it, while all he did was stand around on rom-com posters, leaning against things, but would you listen? No you would not. But I was right, I am the best.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (Wes Anderson, 2014) - A classic to rank alongside Tenenbaums and Rushmore, with two beautiful central performances - as well as fine ones from F. Murray Abraham and Tom Wilkinson - numerous comic high spots and a bewitching evocation of a mythical world not glimpsed on screen since the mighty Lubitsch passed on.

Flesh and the Devil (Clarence Brown, 1927) - It's narratively simplistic, erotically confused and perhaps a little erratically played, but it's a visual feast like little before or since, and a fitting showcase for one of cinema's most beguiling, singular performers.

Three Strangers (Jean Negulesco, 1946) - Allergic to formula, yet richly and enduringly fatalistic in the familiar manner of co-writer John Huston, it's one film you won't forget in a hurry, right down to that classic final scene.

-large-picture.jpg)

Wild Boys of the Road (William Wellman, 1933) - The overall effect is unforgettable, with Frankie Darro exhibiting a raw star power in the lead, and the film tackling its subject head on, anticipating The Grapes of Wrath in its story of desperate people forced to wander aimlessly away from their homes and happiness in search of a living.

Skyscraper Souls (Edgar Selwyn, 1932) and Employees' Entrance (Mervyn LeRoy, 1933) - I'm pretending this is a single film, so I can squeeze in an extra one, though in a way I suppose it is. Two slices of intensely enjoyable Pre-Code entertainment, with Warren William's tyrannical, twinkly-eyed businessmen ruling a skyscraper and then a department store with an iron fist, whilst causing problems for a pair of young couples. Both movies are cynical, malevolent and richly textured, providing a vivid portrait of Depression-era America.

Mary and Max (Adam Elliott, 2009) - An animated Australian wonder that eschews easy sentimentality with admirable vigour, lending the mesmeric Que, Sera Sera sequence a haunting power, before a climactic scene that may even make Max weep big and salty tears.

The Beloved Rogue (Alan Crosland, 1927) - An extravagantly mounted silent version of the story later made as If I Were King, in which John Barrymore - if not approaching his scintillating Shakespearean apex - is at least astonishingly good.

and 10 old ones I still love beyond all measure:

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (Elia Kazan, 1945)

Husbands and Wives (Woody Allen, 1992)

Låt den rätte komma in (Tomas Alfredson, 2008) aka Let the Right One In

Libeled Lady (Jack Conway, 1936)

The Purple Rose of Cairo (Woody Allen, 1984)

Crimes and Misdemeanours (Woody Allen, 1989)

Kes (Ken Loach, 1969)

The Royal Tenenbaums (Wes Anderson, 2001)

if.... (Lindsay Anderson, 1968)

Radio Days (Woody Allen, 1987)

***

Watching this is mostly my life now.

Crazes: Joan Blondell, Pre-Code cinema, Bob Fosse

Continuing preoccupations: John Ford, Woody Allen, Barbara Stanwyck

Stuff I caught up on: A social life, the theatre, Woody Allen films I'd seen before.

Revelations: Ann Dvorak wiping the floor with everyone - even Paul Muni - in Scarface, a film I hadn't seen for a decade.

Happiest surprises: Vera-Ellen's exquisite, exotic dance numbers in the disposable, annoying Danny Kaye comedy, The Wonder Man, were a very rare treat. Joan Crawford not being shit in Flamingo Road was kind of surprising.

Biggest disappointment: I'd always thought Against All Odds sounded kind of fun. It was kind of not any fun. Lubitsch's Madame DuBarry was an example of a deluxe label - in this case Eureka's Masters of Cinema - attempting to re-appraise a film they happened to have got the rights to, but the movie being a tad rubs.

Oddest film: I'm not sure if it was the unnecessary neck brace and robot arms, or their wearer's somewhat misguided approach to wooing, which involved stealing a murderer's arms, but Mad Love. The Hatchet Man ran it a distant second.

Worst films: I saw some absolute dreck. The Boat That Rocked was absolutely hideous. Enchanted April lacked its moral turpitude but not its dearth of any conceivable entertainment value.

Some favourite moments: I must have watched Carol Haney doing Steam Heat in The Pajama Game 50 times. Choreography by Bob Fosse (but of course). The prologue to The Hatchet Man was staggering. The romantic scenes between Franchot Tone and Madeleine Carroll in The World Moves On were as lushly perfect as any I've ever seen, but also contained a rare and durable truth. Once again, though, the Annie Laurie scene from A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was the best thing I saw all year.

2014 was... A year I expanded my horizons beyond the cinema screen. I always come back to it, though, and early December was dominated by movies in the most delightful way.

Best film I saw at the cinema: Boyhood.

I was bored by: Too many things. Seeing the same gag for the entirety of Airplane II felt more like a chore than A Fun Thing to Do.

I wrote this pretty good review of _______________, you should read it if you have a minute:

Total number of films I've seen (new watches in brackets): 197 (151)

***

MUSIC

My pretend girlfriend.

The best concerts I saw this year were, conveniently enough, at work. The pick of the bunch was a mesmerising show by Lebanese electronic grunge pioneer Yasmine Hamdan in the Elgar Room back in June, her visceral, confrontational stage style and startlingly intense, involved vocal delivery cleverly disguising the fact that she was so full of fever she could barely speak above a whisper ahead of the show, and was having to devise new melodies on the spot to compensate for her truncated range. She's also tying with Michael Giacchino as the loveliest person-of-note I've met in my new job. Here she is putting up with me.

*affixes special boasting hat* I also saw Elvis Costello sing Shipbuilding - and an all-star line-up join together for The Auld Triangle - at the Irish State Visit concert, Ceiliúradh, enjoyed a private gig from Swedish country duo First Aid Kit alongside some schoolkids, and watched Van Morrison belt out Sometimes We Cry and then unaccountably do an impression of Joe Pesci during November's BluesFest. But the other three Hall shows that really stood out for me were James Taylor's beautiful, conversational set in October - where he played Sweet Baby James and the obscure, dazzling Millworker - Rufus Wainwright's mesmeric Prom, and Suede playing the whole of Dog Man Star during Teenage Cancer Trust week.

The intense humming of evil never felt so good.

And away from the Hall? Well, if Suede are my favourite band bar none, then The National are my favourite band since then, and though the O2 is - of course - essentially a retail park with no sense of history and a warehouse in the middle of it, I was right down the front where such things matter less. Even wearing my Hall-branded hat, I'll admit that their tour-ending extravaganza was really something quite wondrous. Two weeks later I was at the Roundhouse for the first time, as the group that dominated my teenage years - Manic Street Preachers - played the album that defined them, The Holy Bible, in its mesmerising entirety. Singer James Dean Bradfield had a sore throat, and I left the venue drenched in other men's sweat, but it was a totemic event with complete emotional resonance for me. I'd never expected to hear Of Walking Abortion, Archives of Pain or The Intense Humming of Evil played live and in some ways it felt like a fitting end to that chapter of my life. Then I put the record on the next day.

***

EXHIBITIONS

There's loads going on in London, much of it just around the corner from me on Exhibition Road. The Stranger Than Fiction exhibition - a history of Joan Fontcuberta fakes - was very good and the Rubbish Collection was even better, an improbably entertaining look at everything that the Science Museum had chucked out in a month. But for me, the best three I saw this year were Malevich (Tate Modern), Disobedient Objects (V&A) and Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination (British Library).

Malevich was shown in conjunction with an exhibition of Matisse Cut-Outs. The Matisse was excellent - if a little heavy on fauna, often in the most incongruous places (the Nativity) - especially something like The Acrobats, a joyous celebration of movement made by an artist slipping into paralysis. And yet the Malevich made its rival's flaws readily apparent. Matisse was an artist sponsored by royals, prestigious galleries and big business, lauded everywhere he stepped. Malevich's career took shape in the cauldron of extraordinary social upheaval, with censorship, subjugation and grinding poverty all bleeding into his work. Poverty in the scraps of paper used for sketches, a canvas painted on both sides, and a shelf substituting for a conventional surface for one richly textured work; censorship in the way his topics and style was restricted and dialled back by an unprecedentedly authoritarian government; and subjugation in the way that the exhibition has several missing years, where its subject was simply slung in jail. This remarkably comprehensive exhibition followed every step of his evolution (and some would argue devolution), from derivative daubings to a complete deconstruction of the form - typified by the famous if staggeringly pretentious Black Square - to a final room that I found stunningly effective: the portraits a marriage of his stylistic preoccupations and the tradition of social art that felt less like a compromise than a sly and silent triumph.

.jpg)

The small, perfectly-formed Disobedient Objects charted around 50 years of social activism via blow-up cobblestones, satirical Top Trumps cards and good old-fashioned banners. My favourites were a wall of stickers and flyers collected around London lately ("Be nice to prostitutes," says one), a Burmese bank-note featuring Aung San Suu Kyi within the watermark, and these East Coast puppets, showing American oil billionaires following an Iraqi woman down the street, in her arms the dead body of her child.

Finally, the British Library's accessible, incisive Terror and Wonder charted the growth of Gothicism from The Castle of Otranto to The Wicker Man, via Mary Shelley's manuscript for Frankenstein, news periodicals about Jack the Ripper, and the Whitby goths. All in all, an exquisite treat, though if I hear that 90-second loop from The Bride of Frankenstein one more time, I may scream.

***

THEATRE

I've spent a good portion of this year in the theatre, being an insufferable London luvvie. Plays ranged from a musical revival par excellence (The Pajama Game at Shaftesbury Avenue), to an eye-opening depiction of the struggles facing injured servicemen (The Two Worlds of Charlie F at Richmond Theatre), to a star-led Shakespeare (Richard III at Trafalgar Studios), to a double-bill of Alan Bennett one-acts about the Cambridge Spies (Single Spies at Rose Theatre Kingston), but my favourites were these, in ascending order...

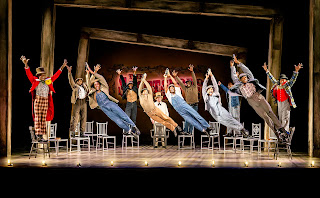

5. The Scottsboro Boys (Garrick Theatre) - A confrontational take on a notorious miscarriage of justice concerning eight African-Americans accused of rape, which tells its story via the cartoonish characterisation, fast-paced double-talk and blackface routines of a minstrel show. Amidst virtuosic tap routines, nostalgic ballads and courtroom theatrics emerges a white-hot, righteous fury, informing the kind of low-key, downbeat ending that lodges in your brain and then just refuses to leave. This symbolically minimalist production took aim at everything from slavery to yellow journalism to the idea of the minstrel show itself: an appropriation and perversion of African-American culture in which experiences are packaged for profit and stripped of their power. At times the broad posturing of the show's two chief comic characters did jar with my own sensibility, but it was also faithful to the genre it was embracing, subverting and then ingeniously corrupting, and the overall effect was of a bold experiment that had paid off almost completely.

4. Let the Right One In (Apollo Theatre) - The best performance I saw this year wasn't on the big screen or the small screen, it was at the Apollo Theatre, where Rebecca Benson's haunting, tender, guiltily vicious take on the genderless, 200-year-old vampire Eli threatened to bring the roof down once more. A Scottish production which had transferred via the Royal Court, it pared down the narrative from the 2008 Swedish vampire flick, cranked up the poignancy and then just let Benson do her thing, which was simply electrifying to behold. Even aside from her otherworldly performance, lit by moments of humour and shocking violence, there was plenty to enjoy, including an imaginative set that allowed for one stunning coup de théâtre, and an effective performance from Martin Quinn as Oskar (who nevertheless seemed a little old), but it was Benson's blood-drenched, contralto theatrics that took this somewhere truly remarkable, and I can't wait to see what she does next.

3. The Drowned Man (Temple Studios/National Theatre) introduced me, somewhat belatedly, to the concept of immersive theatre. Turning a four-storey warehouse near Paddington station into a beach, a seedy bar and a movie studio of indeterminate age, Punchdrunk presented a dizzying story of love, redemption and murder, seen in snippets depending on just where in the vast, sprawling sets you happened to have wondered. I spent quite a bit of trailing an alcoholic, down-on-his-luck bit-part player flogging goods on the side, who got a second shot at the exact moment his life seemed to be over. As he walked into the distance, a mesmeric dance began atop of a caravan, feeding into a sickening ballet of rape and violence, the show degenerating into an orgy of destruction. It was a magnificent achievement and I found its incomplete nature - unique to every patron - a remarkable and enduringly fascinating proposition.

2. Skylight (Wyndham Theatre) - Carey Mulligan is about the best young actor on the planet and this David Hare play was a fitting showcase for her stunning talents, the vein in her temple twitching as her opinionated schoolteacher's life was turned inside out by a man from her past, charismatic capitalist Bill Nighy. While Mulligan, in her West End debut, was a "do gooder" with a self-destructive streak, Nighy's ruthlessness in the world of business was offset by a softness and enduring affection for his former lover that made their scenes a bittersweet dance of denial, recrimination and repair. A couple of references unavoidably dated the play - I'd forgotten that social workers were a tabloid scourge in the mid-'90s - but it drew you inexorably and entirely into its drably beautiful bedsit world, and had a vast amount to say about both our purpose on this planet and the ugly collision between personal and professional lives, thanks to subtly masterful staging, great writing and a pair of utterly exceptional performances.

1. The Book of Mormon (Prince of Wales Theatre) - The best thing I have ever seen in a theatre. Hysterically funny, stingingly satirical and full of the most horrendous earworms. And maggots.

The worst, incidentally, was Ballyturk, the National Theatre's highly embarrassing, meaningless Beckett rip-off. I'm back for Man and Superman in May. Bernard Shaw + Ralph Fiennes cannot possibly fail.

***

BOOKS

I zipped through three of Ben Macintyre's populist, novelistic and sharply written historical bromances - on Kim Philby, Eddie Chapman and Adam Worth - enjoyed Hilary Mantel's dense, epic and labyrinthine Wolf Hall (though it took me an age), and finally got around to Pride and Prejudice, which is just as good as everyone already knows it is. Todd McCarthy's mammoth tome on Howard Hawks was extremely boring and entirely lacking insight into the great director's character, though it remains a useful reference for those delving into the production history of his movies.

The first half of Morrissey's autobiography was pretty good, especially the section on poets like A. E. Houseman, but the second was interminable and extremely hard to like, much like the man himself. Perhaps that's the point, though: did he really need an editor, or is this unfiltered portrait more valuable than a better book might have been? I collected some of the more self-parodical passages here.

Far more enjoyable in the memoir stakes was Hollywood by Garson Kanin, one of the great - if most erratic - screenwriters of his generation. It traverses similar ground to David Niven's Bring on the Empty Horses - insecure starlets, vain swordsmen, anecdotes about Garbo, Chaplin et al - but benefits from Kanin's fusion of blistering wit and appealing self-deprecation, and his interest in the moguls who shaped the industry, particularly Sam Goldwyn, informed by a colourful, scholarly preoccupation with film history. Then at the end he starts getting all dewy-eyed about a brothel, but you can't have everything.

***

TV

Aside from Sherlock - obviously - the year's highlight was GBH, Alan Bleasdale's staggering allegorical drama/thriller/black comedy about stress and socialism, powered by Robert Lindsay's tour-de-force. At the other end of the ideological spectrum, or near it, was The Apprentice, which I finally cottoned onto and which gave me no end of joy, appearing to have a comic genius as an editor. Parks and Recreation's sixth season was the weakest since the first, a whiff of desperation in the nose as it fell back on guest stars, European jaunts and new characters (fuck off Craig), though when it worked, it worked, with Amy Poehler terrific and Chris Pratt still just about the funniest thing on Earth. Brooklyn Nine-Nine had too many bad jokes and weak supporting characters, though Samberg was exceptional and I found the romance astonishingly effective.

***

That's all for this year. Thanks for reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment