FILM

The Mouthpiece (Elliott Nugent and James Flood, 1932) – I have such a soft spot for pre-Code movies, and especially the pungent, abrasive, censor-baiting comedies starring the likes of Lee Tracy (Blessed Event, The Nuisance, Call All Wires!), William Powell (Jewel Robbery, High Pressure) and Warren William (Beauty and the Boss). Though not uniformly, these had a tendency to be extremely funny and cynical, before discovering a latent tenderness that at its best was knitted into the fabric of the film, and at its worst saw the piece unravel into soapy melodramatics. Few, though, were ever as sweet and affecting as this one, in which William’s noble prosecutor reacts to tragedy by reinventing himself as an amoral shyster for the underworld (with a moustache, naturally), only to be changed back by the guileless southern office waif (Sidney Fox) he’s been trying to shag. It’s a little clumsy in places, and mistakes audacity for humour, but it’s saved by the performances.

Fox, a short-lived punchline remembered if at all for her sexual affairs with Universal execs, is hesitant and naïve in a way that might not all be intentional, but works its magic upon you, her innate ethereality, uncompromising morality and unexpected sexual potency convincing us unfailingly that a rich, powerful, overbearing and unapologetically unyielding lawyer would be desperate to sleep with, protect and be forgiven by her. As the lawyer, William dominates as he has to: he’s witty, assured and prepossessing, while allowing self-debasement and self-disgust to bleed into his performance, and he’s supported by the great Aline MacMahon, characteristically brilliant as she turns the somewhat familiar role of the lovelorn, patient secretary into something indelible. In these studio films, MacMahon often gave the impression of having just wandered in from real life: she could have the lightest touch with comedy, and spit out Warner Bros’ snappy zingers, but she was at her best when playing something heavy and truthful and whacked out.

Warren William didn’t star in as many – or as good – tailor-made comic vehicles as Tracy and Powell: his greatest roles were topping the bill in ensemble, state-of-the-nation films like Employees’ Entrance, which bristled with energy, anger and social comment, even if his megalomaniac sex pests powered these movies, and are what you remember of them (indeed, he returned to unrepentantly terrorising virgins in Skyscraper Souls later in 1932). The Mouthpiece is a leaner, slighter and simpler film, which zeroes in on the star, shows him through the eyes of two good women, and allows him an emotional sensitivity that was usually off limits for the pre-Code William. It’s not perfect, but it holds a special place in this cycle of films, and it has several beautiful moments, infused with a sweetness that’s tantalisingly bereft of saccharine or soap.

See also: I read the only existing Warren William biography a couple of years back. He really didn't have a terribly interesting life. For what's it's worth, Powell made a similar film to The Mouthpiece the same year, 1932, the stolid Lawyer Man, which gets a shot in the arm from Joan Blondell's sensitive, erotic performance, but is hampered by for some reason omitting any scenes that take place in a courtroom.

***

TV

"I'm interested in one thing, and only thing only: bent coppers."

Line of Duty: Series 4 (2017) – I wonder if this is the series to which we’ll look back and see that Line of Duty was beginning to go awry*, when a show that traded on an insider feel jettisoned any genuine concessions to realism, and became too daft and melodramatic and big and yet somewhat unconvincingly inter-connected. That’s its overall impact, but this season is packed with memorable characters, so stuffed with incident that it’s jawdropping in the moment, and yet still quietly dominated by Thandie Newton’s performance.

Newton is Roz Huntley, an arrogant, assertive DCI still scrambling to catch up after taking years off to start a family. When she gets the chance to close a serial killing case, she takes it, arresting Michael Farmer (Scott Reid), a learning-disabled loner incapable of riding out the interrogation (as Series 3 dealt with both Operation Yewtree and the Mark Kennedy affair, so this plot-thread appears inspired by another topical case, that of Making a Murderer’s damaged, eager-to-please, patently innocent Brendan Dassey). Enter AC-12, who have a few concerns about the strength of the evidence.

Line of Duty’s central triumvirate – Steve (Martin Compston), Kate (Vicky McClure) and Hastings (Adrian Dunbar) – are fantastic characters, but here they mostly just plod along. Earlier seasons perhaps saddled them with overly soapy subplots, but this time there’s very little character development, beyond the manufacturing of some unconvincing competition between the two junior officers. Things happen to them, but they don’t change.

Despite that, both Compson and Dunbar are excellent, with Hastings’ broiling sense of rectitude cleverly cast into doubt, and Steve’s somewhat squat stoicism – coupled to an impressively realised impetuosity – once more the defining flavour of the series. A mention too for Paul Higgins, memorable as the vituperatively violent Jamie in The Thick of It, whose patronising faux-earnestness pours out in overbearing, over-familiar line readings that might just be brilliant. Certainly his voice becomes a central part of the programme’s atmosphere, its feel and its identity.

Newton is given an exceptionally tricky role, so much of it internalised, so much of her character’s appearance being for the benefit of others, the actress variously asked to mask, contort, unshackle or abruptly unveil her feelings. Sometimes she’s barely allowed to give a performance at all, being asked to keep the audience in a permanent limbo, dropping clues or red herrings instead of inhabiting a role. And yet when it matters, as in that climactic interrogation, in which she suddenly becomes recognisably ‘feminine’ for the first time, she shows why she was an indie darling, Hollywood star and a stellar coup for Jeb Mercurio and co. That level of acting is rare, even in a show as lauded as Line of Duty (and especially compared to fellow guest star Jason Watkins, who has won a BAFTA and an Olivier, but is desperately unpersuasive here).

Series 4 feels like a bit of a dip after three compelling seasons: there are too many scrawny or barely-tied plot threads, its perhaps noble attempts to look at race and sexism come off more like window-dressing – a concession to ‘serious’ television, rather than state-of-the-nation polemicising – and its culprits are obvious in a way that they haven’t been before. But while its total impact is muted by these shortcomings and its sojourn into the incredible, it’s still cracking, addictive TV. Fella. (3)

*like Sherlock's third series, which was great in itself, but had sown within it the seeds of its own destruction

See also: I talked about the first three series here. My statistical survey on BAME characters in Line of Duty being mostly cowards, informers or bent coppers will have to wait, as I've realised that also describes the majority of the white characters.

***

BOOK

Often when the Spectator says something is brilliant, like the free market or Toby Young's new column, they're wrong. They're not wrong here.

A Long Way from Verona from Jane Gardam (1971) – This is such a special book: like Elizabeth Taylor’s Angel (one of my discoveries of this year), its heroine is a brutally honest teenage writer in a vanished England: and an outsider because she isn’t like anyone else. Like Angel, too, it has an innate, fierce unpredictability and a rapturously distinctive voice (ideally utilised in a first person narrative) which, by definition, make it nothing like Angel. Its wartime Yorkshire setting is intrinsic – the story set against the mercilessness and the brutal lottery of war, even on the Home Front – and it crashes into the narrative, but it isn’t a book about war. It’s a book about Jessica Vye and the world she inhabits, ridicules, abhors and attempts to negotiate, with uncertainty and arrogance and perseverance, and a conviction that never shakes, but does latch onto passing whims, and falls prey to her explosive temper. It is fascinating and funny and spectacularly unsentimental, as well as uncategorisable in the best possible way. (4)

***

EXHIBITION

Lenin's lovely manners

Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths (British Library) – I studied Russian history at GCSE, A-level and university (my undergraduate dissertation was on Stalin’s show trials), so I was very excited about the British Library’s exhibition, 100 years on from the revolution. They didn't let me down.

It’s vividly staged – in the space where I saw the Gothicism exhibition in 2014 – with digital screens and photographic lightboxes, all framed in vivid scarlet, enticing you in and guiding you through the story, beginning in a Tsarist Russia of unbelievable inequality, charting the mounting division and discontent, and then exploding into revolution, and the five years of bloodletting that were the Civil War (an oft-overlooked part of the story, dealt with in due detail here). Crucially, Russian Revolution does a formidable job of being a paper-led British Library exhibition without just showing you a lot of books.

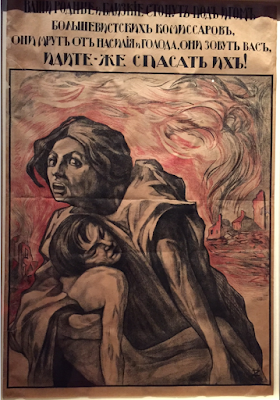

The Whites' propaganda was largely rubs. Here's an exception.

There are books, papers and some irresistibly arresting posters, but also dozens of other artefacts – a Red Army cap; a peasant’s cheap, woven shoes; a wooden gun so alarmingly primitive it induces panic; a free gift given away at the Khodynka Field tragedy, the cheap tankard juxtaposed with one of Tsar Nicholas’s own immaculate regal glasses – listening posts, a giant digital map showing the marauding Red Army’s progress during the Civil War, and a climactic screening room, with Shostakovich on the PA and classic propaganda films by Eisenstein (October) and the Vasilievs (Chapaev, Stalin’s favourite on the big screen).

The greatest excuse of all time.

Now and then the exhibition text is a little drab or clunky, or begins discussing events or institutions before defining what they are, but the wealth of material is astonishing, and I got a particular visceral thrill from seeing the handwritten notes by Trotsky and Lenin – the latter applying under a pseudonym, extremely politely, to be a BL reader in 1902 – as well as those propaganda posters in the constructivist style, much homaged or parodied, but still bracingly and instinctively powerful. Like this one:

That constructivism I bum off so much

My main take-aways:

a) my uncontroversial view that the ‘communist’ experiment in Russia was essentially just a disaster (and one which continues to plague socialist causes) doesn’t look like being challenged any time soon

b) the reviled Tsar Nicholas II, later executed for his crimes against the workers, visited the wounded a day after a tragedy... *whistles*

(4)

***

LIVE

The Best of Elmer Bernstein (aka The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape and more!)

at the Royal Albert Hall, Sun 18 Jun, 2017

This was such a fantastic show, and it’s been a pleasure to work on too, allowing me the chance to luxuriate in the movie music of the incomparable Elmer Bernstein, who has been a favourite since my teens (I often work to his music, particularly The Man with the Golden Arm, a hypnotic, unrelenting jazz offering that simply changed the way movies were scored), and to chat to the great comedy director, John Landis, who worked with Bernstein on 12 films, and was one of the co-hosts of this concert. The other was Peter Bernstein, Elmer’s son and John’s schoolmate, who shared funny, moving stories about his bold, brilliant, blacklisted father, as well as conducting the Royal Philharmonic Concert Orchestra. With Peter on the podium, Landis shamblingly shuffling papers and regaling us with big, well-trodden showbiz tales, and a setlist showcasing Elmer’s pioneering work in everything from epics to comedies, Westerns to romances, and nature documentaries to sweaty, cynical, claustrophobic fag-end noirs, it was cosy, conversational and emotionally overwhelming in turn.

Some of the music was merely pretty and well-played, the show kicking off with a trio of pieces that have no real resonance to me – the theme from the Nat Geo TV show, a suite from The Ten Commandments, and the main title music from the bloated disaster movie, Hawaii, but everything that happened after that was wonderful in one way or another. Bernstein’s rhapsodic homage to/pastiche of classic Hollywood music – evoking the very history of Hollywood and composed for a ‘60s TV show called Hollywood and the Stars – was a revelation, captivating me with its sweeping, Steiner-esque beauty, and was followed by three cast-iron classics. The Man with the Golden Arm rapped and stuttered, its snares and cymbals mirroring the stabbing pain and breathless desperation of addiction (the film’s theme). To Kill a Mockingbird showed Elmer’s innate understanding of cinema, the composer isolating that the story’s raison d’etre is to deal with adult themes from a child’s perspective: the suite, then, for all its tension and frantic menace, is dominated by the music-box cues and elegiac simplicity of his main theme. And The Magnificent Seven, which closed the first half, was an explosion of exuberance: the piece seeming fresh and new all these years, as if heard for the first time. In this setting, one could appreciate not only Bernstein’s instinctive genius, but also his intelligence and craft: the violins leaping up for the final go-round, as the seven ride to the rescue.

I took this picture of the orchestra. It's not very good, is it?

The second half, once more peppered with Peter and Landis’s reminiscences, observations and easy badinage, was a similarly eclectic mixture of unassailable classics and genuine curios. The sleazy but rousing jazz of Walk on the Wild Side was followed by From the Terrace – intended to showcase the ‘romantic’ Bernstein, but a little dull (I know of the film only as an unapologetic Myrna Loy completest) – before a spirited take on the End Title music from ¡Three Amigos!, Landis’s favourite Bernstein score written for him, being that very post-modern thing: a gentle spoof of Elmer Bernstein’s Western scores. After that, we got the director’s favourite Bernstein score of all, a glorious new arrangement of Bernstein’s music for Scorsese’s period drama, The Age of Innocence, followed by a previously unheard – and unused – piece of music written for the transformation scene in An American Werewolf in London (“I used Sam Cooke instead – it took a couple of years, but Elmer forgave me,” as Landis remembered), its pained, violent and discordant death-throes wrapped up in the eerie soundscapes we already know and love. And then it finishes as it must, with an exuberant Great Escape suite, rich in delayed gratification, as we hang on and on for that famous "Dah dah, dah dah dah-la-dah" only to find it fully reclaimed from the dire dirge of an England defeat, and reborn as the triumphant, playful, rousing anthem it once was.

That gets the biggest reception of the night, and so Peter steps back on stage to conduct one more: the scintillatingly sordid Sweet Smell of Success, Bernstein's other great jazz score of the '50s. It's a fitting climax to this celebration of a great artist, which gives us everything we could want, aside from Far From Heaven (my absolute favourite Bernstein score), and salutes his creativity without sugar-coating his personality. Elmer is painted as a man who fought endlessly against pigeon-holing, evaded easy categorisation, and was only able to forge the path he did by taking chances, erecting a wall around himself, and coating his brilliance in an impermeable level of arrogant authority. Bernstein wasn't needlessly abrasive like his predecessor and admirer, Bernard Herrmann (Peter recalls his dad once ringing Herrmann to say thank you for recommending him for a commission, to which the older composer said something along the lines of: "If I didn't think you could do it, I wouldn't have said you could. Now go away"), but from Landis's stories he emerges as a necessarily tough cookie, insulated from creative interference by his crusty self-confidence. I sat there thinking that I'm glad he was, because the cinematic landscape would be a much blander, duller place without him.

Then Landis came back on stage to shout "Go home", so we did. (3.5)

See also: I wrote about my favourite Bernstein piece for the Royal Albert Hall blog here.

***

Thanks for reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment